What do I mean when I say text?

I believe that computing can do more to support our enjoyment of text. I would like to contribute to that realisation. So, I decided to try for a regular blog. Will that help?

This is not to say that text lacks attention or suffers neglect. Rather, I want to make a public commitment that might shame me from giving up, and I want to instigate an effort that might incubate my own contributions. Furthermore, I want to test my ideas. After all, it is easy to be over confident about an idea that you keep to yourself. But, what will I write about? What do I mean when I say text?

By text I mean stuff that rewards reading and enjoys an author. Some obvious examples are books, music, films, and videogames, but also technical writing, diagrams, quips, social bookmarking sites, and so on. Others with greater expertise have examined what it means for a thing to reward reading or enjoy an author, so I need not be definitive. Also, I am happy for the two conditions to depend on one another. For example, I feel untroubled if a thing is more rewarding because I imagine an author for it. Likewise, I am also happy for the decision to be pragmatic. For example, I feel justified in identifying an author and entertaining a certain reading if those decisions lead to to fruitful conversations with others who take a similar view. Since these rules might seem too loose for some, it is worth considering what they rule out and in.

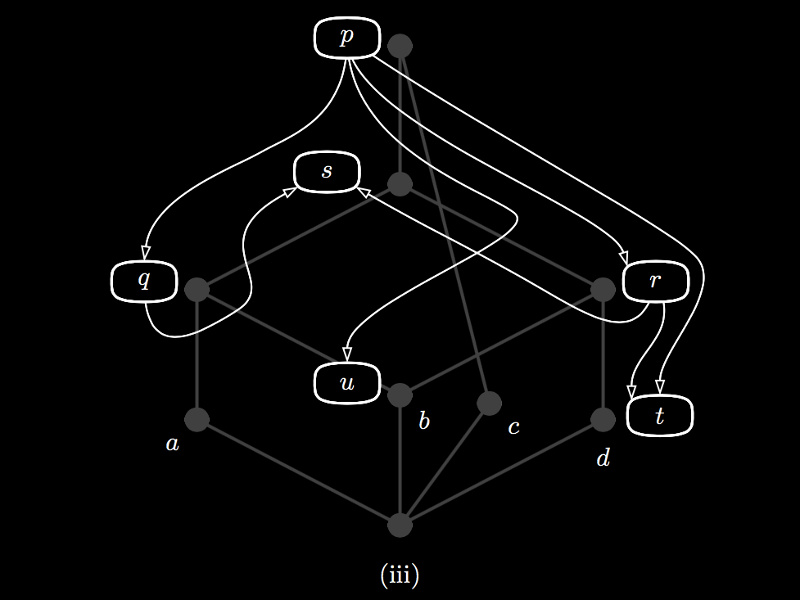

Figure 1. Diagram for an octopus to sit on a chair. Step 3

Let me try and illustrate the difference by two caricatures of data visualisation. In the first, I feel unsettled by the vision of an authorless process that directly identifies actions to take, leaving room only for perception without interpretation. Data visualisation no longer belongs to the realm of text. In the second, I am drawn to the vision of an experimentalist or artist rendering an argument by a repertoire of techniques. Data visualisation is text that an audience reads in the context of what they reckon to be the visualiser’s intent. In practice, the difference between an authorless process and a repertoire of techniques is a matter of degree, and clearly there is a place for both. However, a preference for the second does amount to a different attitude about what we should be doing with computers, and that is the position that I hope to be advancing in this blog.

So if you accept that my loose definition of text is workable, and you accept that a preference for text leads to a different view of what we should do with computers, then you might reasonably have two further questions. Why should I prefer text? What difference does this preference make to computing? I want to finish by making 2 further points on the the first question, and 1 point on the second, which hopefully the blog can say more about over time.

I prefer text, because I find it surprisingly sufficient. This is difficult to characterise, so I am going to limit myself to a few examples. I hope to return to these ideas in later posts. As examples, note the impact of ordinary language philosophy, the experience of writing as thinking, and the extent to which the written word tells of the author. In these examples, we see that text is surprisingly sufficient in the analytic context of philosophy, in the practical context of tackling difficult problems, and even in penetrating the individual. You might reasonably complain that the person at the centre of each example is the author of the surprise, and not text itself. However, what I take from these examples is that the external world of text and the performances that bring it into existence are the real measure of who we are and what we think, rather than some deep interior mental life. This seems to me like an enormous opportunity, and a reason to prefer text.

I prefer text, because it rewards reading. Like a strong wave at the beach, you can feel it twice. First, there is the experience of being an antenna to the signals that it contains, and being carried along by it. Second, there is the experience of discovering that you are affected by it. I want to prefer that opportunity to find myself in relief against another voice. For example, I love reading Homer. The surprise, of breaching deep time to discover that I am bewitched and confused by feelings towards characters who navigate a fantastical world, is only surmounted by the realisation that it is my mundane world that supports this edifice, and that I am really discovering how I feel about my world. However, the reward doesn’t hinge on the exotic. We all love to participate in how-tos and question-and-answer forums on the web. It is wonderful to luxuriate in the details of our small practices spelled out and shared. So, texts are about us, and that is an important thing for a computer to be about.

In my view, computers can do more, because texts are machines. It is easy to see that in the case of videogames. It is a delight of text in our age that we can be so affected by skillfully wrought systems, and videogames that are particularly driven by the interplay of systems are those that I enjoy the most. However, it is easy to overlook the machine like elements of the long standing texts, because: what are narratives but the most elegant Rube Goldberg machines? So let’s make machines to help us make the machines of text, whether systemic, topological, or gloriously sequential.